Do you know how a bicycle works? If asked, could you say where the chain, pedals and frame are? According to a 2006 study by the University of Liverpool, maybe not.

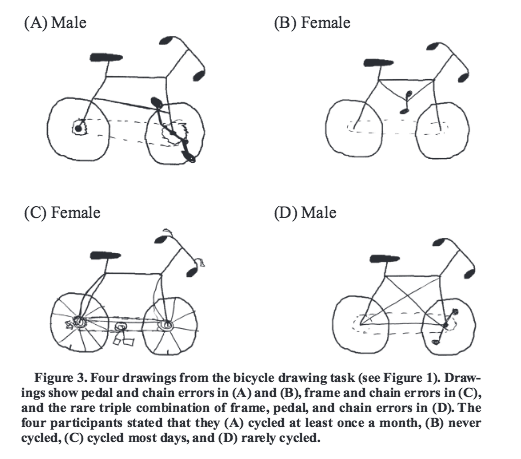

Participants in the study were asked to draw a picture of a bicycle. Later, to make sure that lack of artistic skill wasn’t a factor, they were asked to view pictures with different arrangements of chains, pedals and frames to state which corresponds to a working bicycle.

The result was that over 40% of participants couldn’t do it. Many participants drew bicycles that would be completely non-functional.

It’s amusing to think of what the person drawing these bicycles must have been thinking, such as locking the two wheels together via the frame so it can’t steer, or attaching both wheels to the chain. Before you get too smug, though, try testing yourself. Without looking, could you explain how a can-opener or a zipper works?

This bias—to believe we understand how familiar phenomena work far better than we actually do—is called the illusion of explanatory depth.

This type of overconfidence may be even worse for explanations than it is for remembering facts and trivia. Explanations often have different layers of depth. For instance, you may have correctly remembered that the chain of a bike attaches to the pedals and rear wheel, a relatively superficial explanation. But you may not know how the bike changes gears from the handlebars or how the brakes work, a deeper explanation.

This bias plagues students and knowledge workers, into thinking they understand things they don’t. Worse, the overconfidence sometimes causes people to blame the wrong problem when they can’t perform on tests or tasks.

Why Students (Incorrectly) Fault Memory When They Fail Tests

I get a ton of student emails, and one of the most frequent is a student blaming memory for poor test performance. A typical email would read something like this:

Hi Scott,

I struggle with remembering things for my tests. I understand everything in the class, but when the test comes around I seem to forget all of it. How can I memorize things better?

-Student

On one view, the student isn’t entirely wrong. Failure to produce information for a test can be seen as a failure of memory. But this is misleading, since after this diagnosis, the student decides that the best way to improve is to simply get better at memorizing all the information.

Unfortunately, many of these students are suffering under the same illusion as the participants in the bicycle experiment. They mistake their ability to recognize the logical operation of something with their ability to understand and explain it.

Few people would be baffled as to the function of a bicycle when they see one. For one, the object is too familiar to be surprising. Second, the operation seems readily transparent to inspection. You can push a pedal, see how the chain moves and how that rotates the back wheel.

But this ability to recognize and probe an object in front of you, is very different from the ability to correctly explain the object when it is out of sight.

The solution? Self-testing and tools like the Feynman Technique. Only by forcing yourself to explain does it become apparent how little you understand. Practicing explanations is also the key to form the kinds of memory you need to perform later.

Students suffer from this tendency very obviously, but I believe this also applies as a logical extension to many areas of knowledge work. Often the tendency is to believe because you’re familiar with something that you necessarily understand how it works. While that ignorance may not be a detraction for routine usage, it does impede creative solutions for novel problems.

My theory: good students (as well as programmers, designers, writers, etc.) cultivate a curiosity to test their own understanding of familiar things which combats the illusion of explanatory depth and builds expertise.